04/20/2025:

Resolving Issues with Your Boss (Part 16B):

Synthesizing SPIN and Principled Negotiations

Summary of Part 16A

Part 16A was the first part of a two-part examination of applying Fisher and Ury's Principled Negotiations model as a workplace strategy that helps organizations and employees address potential conflicts before they escalate. The section outlined the history of Principled Negotiations, its core principles, and its successful application in high-level contexts. It concludes by noting the disparity in workplace application due to time constraints, lack of training, and prioritizing expediency over collaboration.

Introduction

Asking the right question at the right time is unquestionably key to the resolution of conflict. I have presented each conflict resolution strategy separately out of necessity: (1) to give credit to each of their originators and (2) to present each strategy in a logical sequence. While all the strategies presented can support each other’s weaknesses, SPIN and Principled Negotiations are particularly so. When used together in tandem, the whole is much greater than the constituent parts.

Part 16B will examine the potential of synthesizing SPIN and Principled Negotiations.

Principled Negotiations Overview

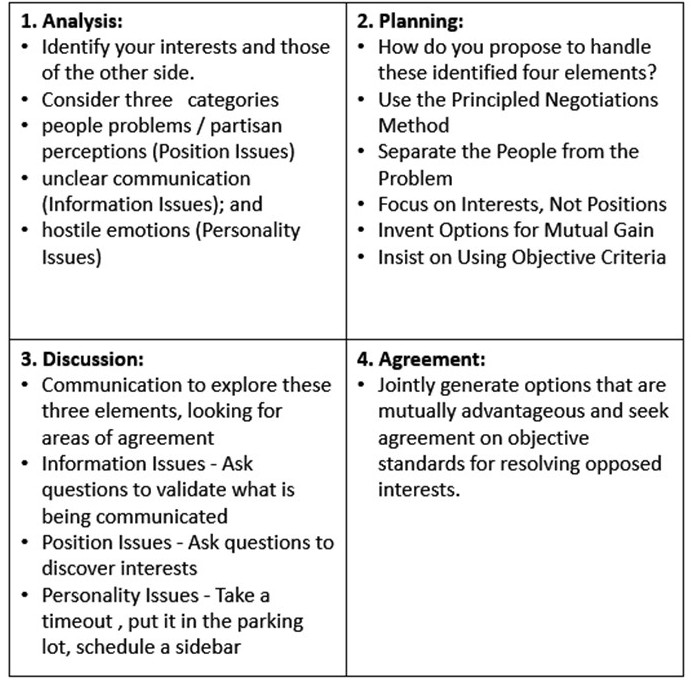

Fisher & Ury’s perennial bestseller, Getting to Yes (1981), expanded on Fisher’s earlier concept of “yesable” propositions from a decade earlier. The authors systematically provided "a framework for thinking and acting" (Ibid., p. 153) when conducting negotiations. They presented four Principled Negotiations stages: Prenegotiation Analysis, Planning, Discussion, and Agreement (see Figure 1).

The Analysis phase involves step-by-step prenegotiation identification of interests by identifying position issues (Ibid., pp. 3–14), communication issues (Ibid., pp. 32–39), and personality-based issues (Ibid., pp. 73, 79). The Planning phase provides a step-by-step approach to applying core principles, such as separating people from the problem (Ibid., pp. 3–14), focusing on issues rather than positions (Ibid., pp. 32–39), inventing options for mutual gain (Ibid., pp. 29–32), and establishing objective criteria (Ibid., pp. 29–32, 81–94). The Discussion phase explores areas of agreement through validation (Ibid., p. 34), probes for mutual areas of interest (Ibid., pp. 44–52), and disengages from personality issues (Ibid., pp. 107–116). The Agreement phase jointly generates mutually advantageous agreement options (Ibid., pp. 65–80).

Figure 1: Principled Negotiations (Fisher & Ury)

Fisher and Ury provide a detailed methodology that includes separating the substance of issues from emotions and perceptions. They prescribe focusing on the parties' underlying interests rather than their negotiating positions alone. They emphasize analyzing those interests to identify shared concerns and needs that might become the nexus for an eventual agreement. They suggest brainstorming options that provide advantages for both sides and searching for objective criteria to evaluate alternatives rather than relying on a contest of wills. They also discuss approaches to reaching an agreement despite unequal bargaining power, a refusal to negotiate, or the use of deceptive tactics.

The Principled Negotiations method relies on four fundamental concepts: People, Interests, Options, and Criteria. Separating the people from the problem (Ibid., pp. 17–39). Focusing on interests rather than positions (Ibid., pp. 44–55). Creating options to allow parties to achieve mutual gain (Ibid., pp. 56–80). Insisting on the use of objective criteria (Ibid., pp. 81–94).

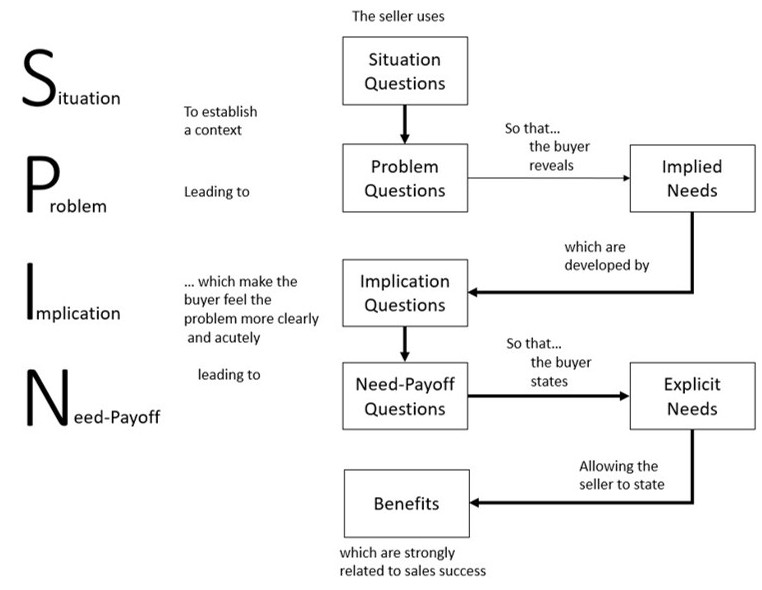

SPIN

Rackham’s SPIN Selling primarily focuses on selling. The original Huthwaite, Inc. research insights reveal how Situation and Problem questions uncover underlying “Needs.” Though different terminology is used, the SPIN strategy mirrors the Analysis, Planning, Discussion, and Agreement stages of Principled Negotiations, emphasizing a communication-oriented process to uncover mutually advantageous agreement options.

Figure 2: SPIN Model (Rackham, 1988, p. 92)

Rackham lays out the basic SPIN approach:

1. Ask “Situation Questions” to establish context.

2. Lead with “Problem Questions” so that the buyer reveals “Implied Needs.”

3. Develop these through “Implication Questions.”

4. Encourage the buyer to state “Explicit Needs.”

5. Allow the seller to present “Benefits” related to Need-Payoff success.

While Rackham provides examples of implementing the strategy, his focus remains on salespeople. Like Fisher and Ury, he does not address what happens after formalizing a contractual agreement. Implementation is left as being someone else’s problem.

However, once an agreement is made, a contract is signed, and handshakes are exchanged, the work is just starting. New problems emerge, critical dependencies arise, and active cooperation is essential. Partisan perceptions, underlying hostilities, coordination constraints, and resistance to participation continue and must be dealt with daily.

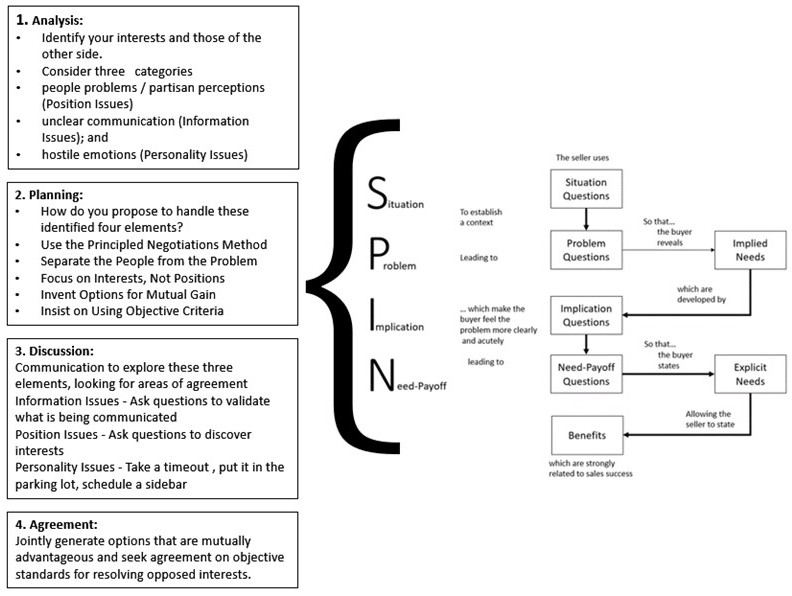

A Synthesized Model

The effectiveness of this synthesized model depends on the circumstances. Even though humans frequently negotiate, many daily interactions are transactional, based on hierarchy and power relationships. Asking well-framed questions initiates a negotiation dialogue by demonstrating understanding, increasing trust, and eliciting critical information.

While neither SPIN nor Principled Negotiations alone provides a comprehensive solution, a structured approach integrating SPIN’s questioning with Principled Negotiations’ resolution framework provides a powerful method for navigating conflicts and ensuring successful outcomes—not just at the negotiation table but also through implementation.

Figure 3: Synthesized Rackham / Fisher-Ury Strategy

The synthesized strategy is as follows:

The Analysis phase involves collecting information about the other party and yourself, attempting to understand everyone’s underlying interests and problems, not their positions. It is conducted in three separate phases:

1. Use situation questions to gather background information about the conflict context, and then use problem questions to identify their pain points and challenges. The information should be based upon hard data, including available documents, not on conjecture or psychological projection. Consider those “people problems” previously discussed, unclear communication, and emotional barriers that may impact their worldview.

2. Assess your pain points, challenges, and perceptions using the same methodology, with the same if not more rigor.

3. Document your assessments in a side-by-side matrix and look for areas of commonality or agreement.

The purpose of the Planning phase is to further refine the issue framing through issue questions directly addressed to the other party. Introducing implication questions emphasizes urgency. The core principles of separating people from the problem, focusing on interests, not positions, inventing options for mutual gain, and insisting on using objective criteria are applied. Use this information to update your areas of commonality or agreement matrix.

The purpose of the Discussion phase is to explore and test positions. Using the expanded use implication questions to make the problem more tangible, introduce need-payoff questions to shift the focus toward solutions. Use SPIN questions to verify what’s being communicated and validate concerns. Use need-payoff questions to discover real interests hidden behind demands. If emotions escalate, pause the discussion, schedule a sidebar, or refocus on objective standards.

By reaching and validating mutually beneficial terms, an Agreement can be reached. Using need-payoff questions, reinforce how the solution meets both sides’ needs to secure agreement buy-in. Jointly generate agreement options before locking into a final agreement or solution. Cite the agreed-upon objective standards used and how they will be jointly monitored. Set up the monitoring or follow-up mechanisms, stipulating who is responsible for what.

Document the agreement.

Conclusion

Integrating SPIN questioning techniques with Principled Negotiations offers a powerful approach to resolving conflicts. By systematically uncovering underlying interests, asking strategic questions, and focusing on mutual benefits, negotiators can transform potentially adversarial interactions into collaborative problem-solving experiences. This synthesized model transcends traditional negotiation methods, providing a flexible framework that emphasizes understanding, trust, and creative solution-finding across various contextual scenarios.

* Note: A pdf copy of this article can be found at:

https://www.mcl-associates.com/downloads/resolving_issues_with_your_boss_part16B.pdf

References

Ade, T., Volz, G., & Zerres, C. (2018). Mind-set-oriented negotiation training: Fostering integrative agreements through collaboration, curiosity, and creativity. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 11(4), 287–309.

Fisher, R., & Ury, W. (1981). Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin Company.

Fisher, R. (1971). Basic Negotiating Strategy: International Conflict for Beginners. London: Allen Lane the Penguin Press.

Oh, A., & Chung, C. (2020). The effects of power and perspective-taking on negotiation outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(7), 654–669.

De Dreu, C. K. W., Weingart, L. R., & Kwon, S. (2000). Influence of social motives on integrative negotiation and problem-solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(5), 889–905.

Rubin, J. Z., & Brown, B. R. (1975). The social psychology of bargaining and negotiation. Academic Press.

Yang, H., & Song, R. (2018). The impact of emotional intelligence on negotiation effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(6), 720–741.

© Mark Lefcowitz 2001 - 2025

All Rights Reserved