12/22/2024:

Resolving Issues with Your Boss (Part 5):

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

Summary of Part 4

Part 4 of this series discussed the nature of humanity and how it is rooted in our constant drive to meet personal needs, desires, and aspirations within the framework of complex and often contradictory social norms. As social creatures, humans rely on cooperation, competition, and problem-solving to navigate the world. Our survival and progress depend on resolving problems, building alliances, and asserting control over our environments. However, these interactions are rarely simple, as they involve a balance of competing interests.

In the context of conflict, our tendencies toward cooperation and competition can either foster resolution or fuel division, depending on how we manage our behavior.

An Introduction to the Prisoner’s Dilemma

We have discussed the broad range of potential human behaviors and why humans behave as they do. We have addressed the need to take responsibility for controlling our emotions and actions. However, before discussing specific dispute resolution and tension-reduction strategies, we must first provide a framework for discussing conflict and its opposite condition: cooperative behavior.

We must explore the two-by-two matrix that conflict theorists use to discuss conflict and cooperative choices and the metaphor now commonly used to think and study such behavior: the prisoner’s dilemma.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is one of the most well-known Game Theory models of human behavior. It offers profound insights into decision-making, cooperation, and conflict-resolution strategies and tactics.

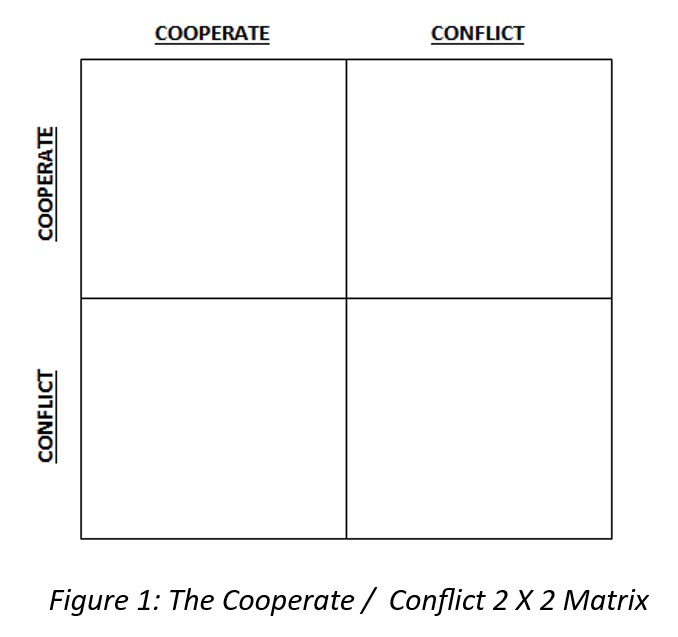

The matrix shown in Figure 1 provides a simple graphical representation of the possible outcomes of a two-person interaction. It consists of a two-by-two matrix, creating four quadrants. The upper left quadrant represents the scenario where both individuals choose to cooperate. The two adjacent quadrants illustrate situations where one person decides to cooperate while the other does not. Finally, the lower right quadrant depicts the outcome when both individuals opt not to cooperate.

See below Figure 1: The Cooperate / Conflict 2 X 2 Matrix

The conceptual roots of the metaphor trace back to the early developments of game theory in the mid-20th century. Game theory emerged as a formal discipline with the publication of Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944) by mathematician John von Neumann and economist Oskar Morgenstern. Their groundbreaking work established a mathematical framework for analyzing strategic interactions. The Prisoner's Dilemma, however, was explicitly formulated six years later by mathematicians Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher (1950) at the RAND Corporation during their research on cooperative strategies in the context of Cold War strategy and military decision-making.

Albert W. Tucker (1950) popularized the scenario and gave it its current name that same year, modifying the narrative to make the abstract concepts used by the previous authors more relatable.

The Prisoner's Dilemma illustrates a paradox where individuals acting in self-interest often fail to achieve the best outcome, showing the tension between personal gain and collective well-being. This simple situational construct has become a cornerstone of game theory and serves as a metaphor for various real-world dilemmas in economics, politics, and social interactions.

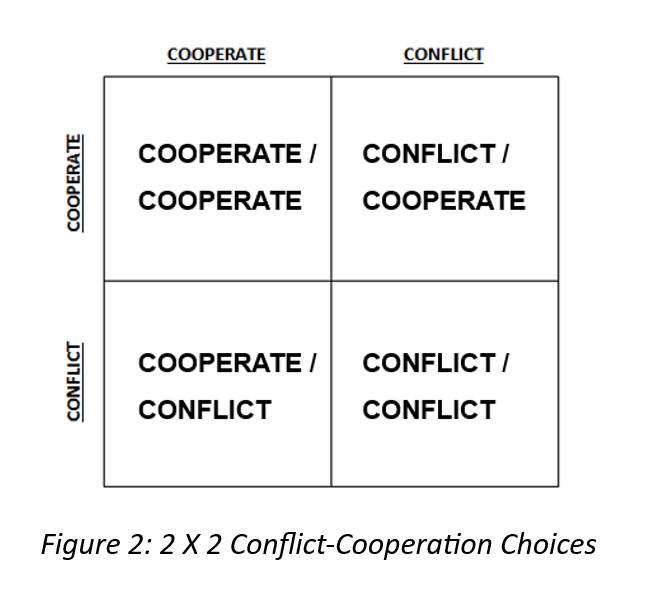

See below Figure 2: 2 X 2 Conflict-Cooperation Choices

As seen in Figure 2, Tucker's version of the dilemma, commonly used in academic discussions, involves two prisoners accused of a crime. They are kept separate and must decide whether to cooperate by remaining silent or betray the other by confessing to the authorities. If both betray each other, they receive moderate sentences. If one betrays while the other remains silent, the betrayer goes free while the silent partner gets the harshest punishment. If both cooperate by staying quiet, they receive minimal sentences. The dilemma demonstrates that rational self-interest can lead to betrayal, resulting in worse outcomes for all involved, as individuals act in ways that undermine collective success.

The Experiment

The traditional Prisoner’s Dilemma experiment explores decision-making by placing the two participants in a scenario where they must each independently choose to cooperate or to compete actively.

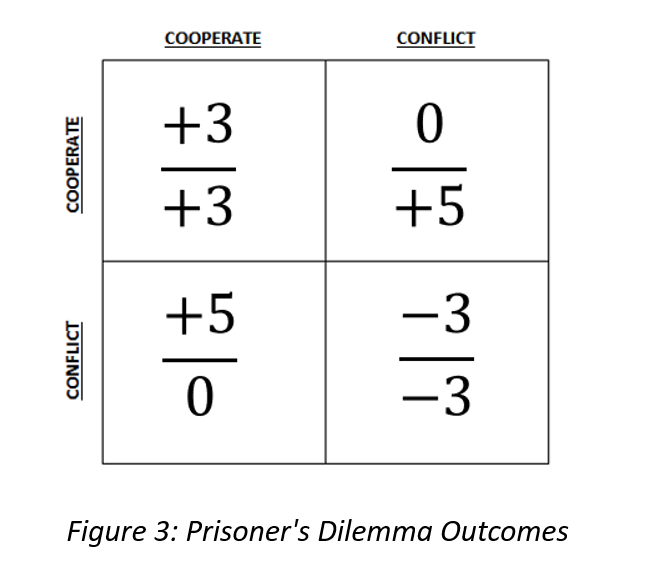

See below: Figure 3: Prisoner's Dilemma Outcomes

The payout structure in the Prisoner’s Dilemma experiment creates an apparent conflict: pursuing individual self-interest often appears more attractive than cooperating, regardless of the other participant’s decision. However, this strategy leads to a collectively worse outcome if both choose to compete. Participants experience firsthand the consequences of these choices, illustrating how short-term self-interest can undermine potential long-term benefits.

Experimental Outcomes

In Prisoner's Dilemma experiments, participants face a choice between cooperation and competition, with the outcomes depending on both players' decisions. These experiments consistently reveal that in one-time interactions, individuals tend to prioritize competition as it minimizes personal risk regardless of the partner's choice. However, in repeated interactions, cooperation becomes more prevalent, driven by recognizing long-term benefits and the opportunity to build trust.

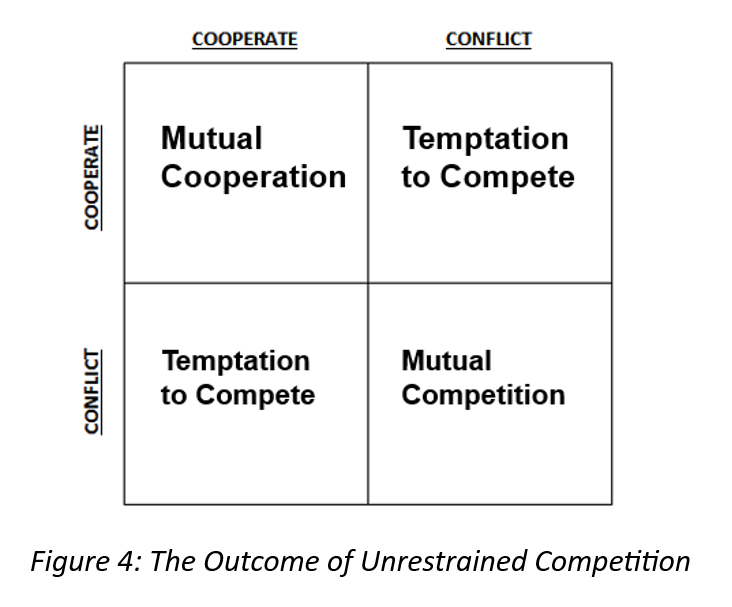

See below: Figure 4: The Outcome of Unrestrained Competition

The findings emphasize the importance of reciprocity in maintaining cooperation over time. Strategies like Tit-for-Tat—cooperate first, then mimic the partner's previous move—have proven highly effective. These strategies balance reward and punishment, encouraging mutual collaboration while deterring consistent competition. Forgiveness is also a critical element in sustained cooperation. Strategies that allow occasional competition but return to the partnership after trust is re-established tend to outperform rigid approaches.

Communication plays a pivotal role in these experiments. When participants are allowed to communicate, cooperation rates increase significantly. Discussions enable players to align their strategies, establish trust, and clarify expectations. Conversely, lacking communication often results in misunderstandings, mistrust, and higher competition rates. These findings highlight the strategic value of clear, open communication in fostering collaboration in workplace environments, particularly in scenarios involving interdependent teams or partnerships.

The framing and context of decisions also influence outcomes. Experiments show that cooperative behavior increases when participants perceive the scenario in a communal or collective context. For example, labeling the game as a "Community Game" rather than a "Wall Street Game" encourages participants to focus on shared benefits rather than individual gain. These findings illuminate workplace culture, where framing tasks as collective efforts can promote teamwork and reduce self-serving behaviors.

Incentive structures are another critical factor. Moderate stakes encourage greater cooperation, as participants perceive the risks and rewards as balanced. However, when stakes are excessively high, fear of loss often drives individuals toward competition. Workplace incentive systems can mirror this dynamic, suggesting that performance-based rewards should strike a balance to encourage collaboration without fostering counterproductive competition.

Cultural and individual differences observed in Prisoner's Dilemma experiments also inform workplace strategies. Cultures with strong norms of trust and collective action tend to exhibit higher cooperation rates, suggesting that fostering a culture of mutual accountability can enhance team performance. Similarly, individuals with traits like empathy or altruism are more likely to cooperate, underscoring the importance of recruiting and developing employees who prioritize collective success over personal gain.

The iterative nature of Prisoner's Dilemma experiments demonstrates the long-term advantages of building and maintaining trust. In the workplace, strategies prioritizing consistent reciprocity and forgiveness, even after occasional failures, can create a resilient foundation for collaboration. By fostering an environment where trust and open communication are valued, organizations can leverage the strategic insights from these experiments to enhance teamwork, resolve conflicts, and achieve sustainable success.

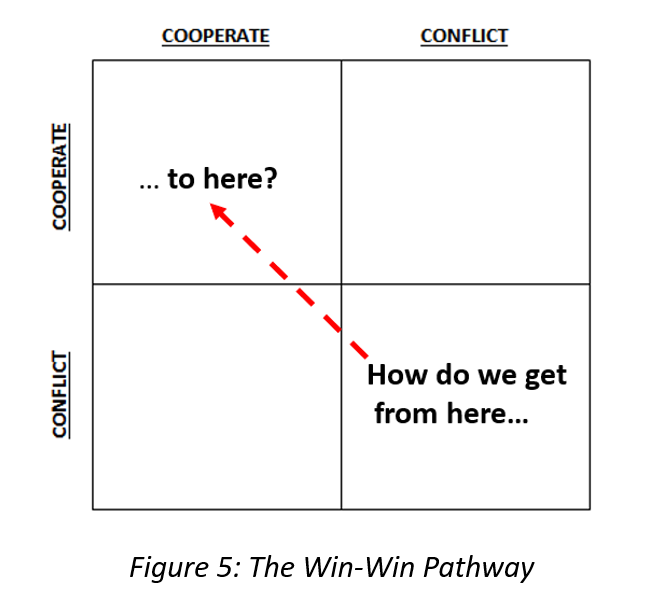

See below: Figure 5: The Win-Win Pathway

The crucial question is: How can humans realistically move from problem-solving strategies primarily based on conflict and competition to strategies primarily based on cooperation and collaboration?

Conclusion

The Prisoner's Dilemma offers a powerful framework for understanding human behavior, particularly when individual self-interest conflicts with the collective good. This paradox demonstrates that while individuals acting in isolation may choose strategies that maximize personal benefit, these decisions often lead to worse outcomes for both parties. As we explore practical conflict resolution strategies, the Prisoner's Dilemma serves as a critical lens through which we can better understand the dynamics of cooperation and competition.

By examining repeated interactions, cooperation becomes more likely over time, especially when strategies like Tit-for-Tat are employed, fostering a balance of mutual respect and trust. The role of communication, framing, and incentive structures further highlights the importance of creating environments where collaboration is encouraged, and self-interest does not undermine collective success.

Ultimately, the lessons drawn from this theoretical model are deeply relevant in real-world scenarios, including workplace settings where teamwork, trust, and clear communication are vital for long-term success. Thus, the Prisoner's Dilemma enriches our understanding of conflict and provides the foundation for strategies that promote cooperation and conflict resolution in complex, interdependent systems.

It reminds us that the binary choice of cooperation or non-cooperation is always present. When cooperation is not the optimal choice, we are still tasked with finding a pathway that leads to a win-win outcome.

* Note: A pdf copy of this article can be found at:

https://www.mcl-associates.com/downloads/resolving_issues_with_your_boss_part4.pdf

References

Axelrod, R., & Hamilton, W. D. (1981). The evolution of cooperation: A quantitative model of the prisoner’s dilemma game. Science, 211(4489), 1390-1396.

Burton, J., & Volkan, V. (2014). Conflict resolution in multicultural societies. International Journal of Conflict Management, 25(3), 266-282.

Carrington, P. J., Scott, J., & Wasserman, S. (2005). Interdependence and the structure of social networks. Social Networks, 27(1), 1-22.

Cook, K. S., Hardin, R., & Levi, M. (2005). Social norms and their implications for conflict resolution in contemporary American society. American Sociological Review, 70(3), 381-404.

Goleman, D. (2010). Leadership and conflict resolution: The role of emotional intelligence. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 18(3), 248-262.

Guerrero, L. K., & Andersen, P. A. (2003). The role of self-awareness in resolving interpersonal conflicts. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 31(4), 308-324.

Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (2006). Emotional intelligence and interpersonal behavior. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1(1), 183-204.

McCarty, C. S., & Kincaid, J. D. W. (2009). Education for conflict resolution: Theory and practice. Journal of Peace Education, 6(2), 177-193.

Moore, C. W. (2014). Transforming conflict through collaborative negotiation. Negotiation Journal, 30(2), 179-189.

Figures:

© Mark Lefcowitz 2001 - 2025

All Rights Reserved

© MCL & Associates, Inc. 2001 - 2025

MCL & Associates, Inc.

“Eliminating Chaos Through Process”™

A Woman-Owned Company.

Business Transition Blog

No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise), or for any purpose, without the express written permission of MCL& Associates, Inc. Copyright 2001 - 2025 MCL & Associates, Inc.

All rights reserved.

The lightning bolt is the logo and a trademark of MCL & Associates, Inc. All rights reserved.

The motto “Eliminating Chaos Through Process” ™ is a trademark of MCL & Associates, Inc. All rights reserved.

While listening to an audiobook on the Medici by Paul Strathern, I was presented with a historical citation that I knew to be incredibly inaccurate. In a chapter entitled, "Godfathers of the Scientific Renaissance". discussing the apocryphal tale of Galileo's experiment conducted from the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the author cites Neil Armstrong in the Apollo 11 flight to the Moon with its memorable modern recreation, using a hammer and a feather.

Attributing this famous experiment to Armstrong on Apollo 11 is incorrect. It occurred on August 2, 1971, at the end of the last EVA of Apollo 15, presented by Astronaut Dave Scott. To press the point further, Scott used a feather from a very specific species: a falcon's feather. This small piece of trivia is memorable since Scott accompanied by crew member Al Worden arrived on the Lunar surface using the Lunar Module christened, "Falcon".

In an instant, the author's faux pas – for me -- undercut the book's entire validity. In an instant, it soured my listening enjoyment.

Mr. Strathern is approximately a decade my senior. As a well-published writer and historian, it is presumed that he subscribes to the professional standards of careful research and accuracy. Given this well-documented piece of historical modern trivia, I cannot fathom how he got it so wrong. Moreover, I cannot figure out how such an egregious error managed to go unscathed through what I assumed was a standard professional proofreading and editing process.

If the author and the publisher’s many editorial staff had got this single incontrovertible event from recent history wrong, what other counterfactual information did the book contain?

What is interesting to me, is my own reaction or -- judging from this narrative – some might say, my over-reaction to a fairly common occurrence. Why was I so angry? Why could I not just shake it off with a philosophical, ironic shake of the head?

And that is the point: accidental misinformation, spin and out-and-out propaganda -- and the never-ending stream of lies, damned lies, and unconfirmed statistics whose actual methodology is either shrouded or not even attempted -- are our daily fare. At some point, it is just too much to suffer in silence.

I have had enough of it.

God knows I do not claim to be a paragon of virtue. I told lies as a child, to gloss over personal embarrassments, though I quickly learned that I am not particularly good at deception. I do not like it when others try to deceive me. I take personal and professional pride in being honest about myself and my actions.

Do I make mistakes and misjudgments personally and professionally? Of course, I do. We all do. Have I done things for which I am ashamed? Absolutely. Where I have made missteps in my life, I have taken responsibility for my actions, and have apologized for my actions, or tried to explain them if I have the opportunity to do so.

For all of these thoughtless self-centered acts, I can only move forward. There is nothing I can do about now except to try to do grow and be a better human being in all aspects of my life. That's all any of us can do. I try to treat others as I wish to be treated: with honesty and openness about my personal and private needs, and when I am able to accommodate the wants and needs of those who have entered the orbit of my life.

We all have a point of view. Given the realities of human psychology and peer pressures to conform, it is not surprising that I or anyone else would surrender something heartfelt without some sort of struggle. However, we have a responsibility to others -- and to ourselves -- to not fabricate a narrative designed to misinform, or manipulate others.

Lying is a crime of greed, only occasionally punished when uncovered in a court of law

I am sick to death with liars, “alternative facts” in all their varied plumages and their all too convenient camouflage of excuses and rationales. While I am nowhere close to removing this class of humans from impacting my life, I think it is well past the time to start speaking out loud about our out-of-control culture of pathological untruthfulness openly.

Lying about things that matter -- in all its many forms, both overt and covert -- is unacceptable. When does lying matter? When you are choosing to put your self-interest above someone else’s through deceit.

Some might call me a "sucker" or "hopelessly naive". I believe that I am neither. Our species - as with all living things -- is caught in a cycle of both competition and cooperation

We both compete and cooperate to survive.

There is a sardonic observation, “It’s all about mind over matter. If I no longer mind, it no longer matters”. This precisely captures the issue that we all must face: the people who disdainfully lie to us – and there are many – no longer mind. We – the collective society of humanity no longer matter, if for them we ever did.

We are long past the time when we all must demand a new birth of social norms. We all have the responsibility to maintain them and enforce them in our own day-to-day lives. Without maintaining the basic social norms of honesty and treating others as you wish to be treated in return, how can any form of human trust take place?

Listen to the audio