12/22/2024:

Resolving Issues with Your Boss (Part 6):

The Art of Asking the Right Question

Summary of Part 5

Part 5 explored the Prisoner's Dilemma, a classic game theory model that illustrates the conflict between individual and collective interests. In the scenario, two individuals must choose between cooperation and betrayal. While rational self-interest often leads to mutual betrayal, cooperation would yield a better outcome for both. This dilemma highlights the importance of communication, incentives, and cultural factors in fostering collaboration.

By understanding the dynamics of the Prisoner's Dilemma, we can better navigate real-world situations where individual and collective goals may clash.

The Importance of Questions

The philosophical interrogatory, "What is a question?" is virtually unexplored within what has been passed down to us from ancient philosophical thought up to and including the present. Both Felix Cohen (1929) and Lani Watson (2021), writing nine decades apart, expressed surprise at the limited scholarly attention given to what would seem to be a fundamental social and epistemic issue.

Philosophical inquiry often serves as a foundation for other forms of inquiry, guiding and shaping the development of fields like science, ethics, and political theory. While philosophical questions can lead to further investigation in various disciplines, such as by developing scientific methods or ethical frameworks, this process is not always linear. Other forms of inquiry, mainly empirical science, may sometimes evolve independently of philosophical reflections driven by practical goals or technological advances.

This may be the case in conflict analysis and dispute resolution strategies and tactics. While I respect the philosophical approach to this issue, I believe that a practical, functional approach may provide a clearer understanding of what a question truly is and is not. Observing discrepancies between an individual’s words and identifying discrepancies in actual behavior is a better guide to asking the next follow-up question.

Feelings and How We Communicate

In fields ranging from medicine and law to construction and business, we frequently encounter situations where the application of knowledge involves human interaction and communication. Understanding the emotional and psychological states of those involved—patients, clients, or colleagues—can make or break success. The challenge, however, is that achieving clarity in such interactions is not always straightforward. Often, the intricacies of one's emotions, drives, and desires, as well as those of others, are not immediately visible or easily articulated.

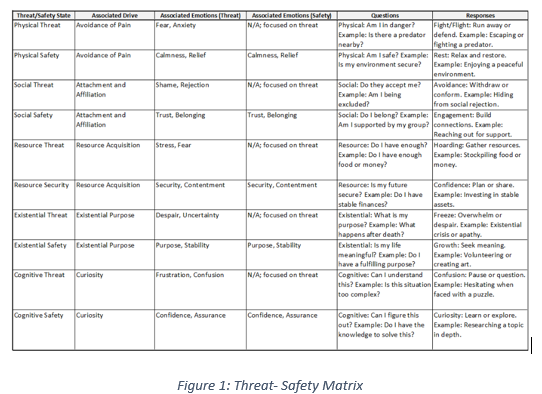

See below Figure 1: Threat - Safety Matrix

We have already discussed how emotions are our brain attempting to predict our present state

based on our basic human drives, our understanding of the current situation, and our past experiences. We have also discussed how important it is to understand and control our emotions. We have discussed how important it is to appraise our feelings and how important regulating our emotions is to dispute resolution and tension-reduction efforts.

Figure 1 displays the Threat/Safety matrix, which categorizes states of threat and safety into specific domains and associates them with key psychological drives, emotional responses, diagnostic questions, and behavioral reactions.

An overview of the key components is as follows: 1). the Threat/Safety State column is divided into Physical, Social, Resource, Cognitive, and Existential categories; 2). The Associated Drives column lists the specific psychological drivers applicable to each Threat/Safety State; 3). The two adjacent Associated Emotions columns (respectively, Threat and Safety) list the typical Threat and Safety emotions experienced when either a threat or safety is perceived; and 4) the adjacent columns for sample individual Diagnostic Questions and typical human behavior examples.

Paul Gilbert (2024, p. 455) points out the distinction between "safety" and "safeness." Threats are not only external; they are also connected to our internal experiences, including our thoughts, fantasies, emotional fluctuations, traumatic flashbacks, and challenges in processing complicated feelings. We are all capable of keeping ourselves in a perpetual state of chronic stress and threat arousal through threat anticipation and safety checking.

Of course, all models are only approximations of reality. Theories, frameworks, and systems, whether they concern social dynamics, economic trends, or even the intricacies of human emotions, offer simplified representations of the complex world in which we live. The inclusion of Figure 1 serves only as a reminder of the complexity of human behavior and a forerunner of our upcoming discussions on tension-reduction strategies to follow in subsequent talks.

Knowledge is invaluable but only genuinely transformative when applied to real-world scenarios. Yet, to effectively apply knowledge, understanding the human components—our goals, desires, emotions, and behaviors—is essential. These elements are often subjective, fluid, and nuanced, making them difficult to capture within rigid models or frameworks—a point where the art of asking the right question becomes crucial.

Asking the right question is never a simple task.

Asking Questions to Define Our Circumstances

Asking and evaluating questions for accuracy or the necessity of asking follow-up questions is how humans define our general and specific circumstances and conditions. Regardless of circumstance and context, we ask questions to gather information, clarify ambiguities, and elicit responses to help us make informed decisions. In this sense, questions are tools for defining and navigating the complexities of social life.

However, asking the right questions in the correct sequence requires sophisticated skill sets. The phrasing of a question can significantly impact the nature of the response we receive. For example, a well-placed question can reveal emotions that someone may not have consciously acknowledged, while a poorly phrased question may shut down communication or lead to misleading answers. Additionally, the same question, under a slightly different set of circumstances, may elicit a completely different response. Humans constantly navigate many emotional and psychological states, often profoundly influenced by our underlying drives. These drives—ranging from the need for physical safety to the need for social belonging or existential meaning—are tied intricately to our emotional responses.

Our drives are the motivational forces that push us to act, seek comfort, or avoid pain. Emotions are often the feedback mechanism that signals when these drives are being fulfilled or frustrated. In this sense, the act of asking questions becomes even more critical. By asking the right questions, we can better understand our emotional states and those of others, paving the way for more effective communication and conflict resolution.

When Is a Question Not a Question?

Asking questions takes time—often more time than circumstances allow or others are able or willing to provide.

Humans have various ways of seeking agreement or validation without genuinely seeking information. One common tactic is the "leading question," designed not to elicit a genuine answer but to guide the respondent toward a predetermined conclusion. A leading question may suggest an expected answer or assume the existence of disputed facts or premises that have not been established. In these cases, questions serve more as a tool for manipulation than for gathering information.

The interrogative: "Don't you think the defendant should be held accountable for their actions?" is a leading question because it implicitly suggests that the defendant is guilty and that accountability is the appropriate response. The questioner is not genuinely seeking the respondent's opinion; instead, they are trying to push the respondent toward a specific stance. Similarly, a question like "Why do you always fail to meet deadlines?" assumes that the respondent consistently fails; any response given implicitly accepts the premise to be true. In both instances, the question acts more like a statement to guide or influence the answer than a genuine inquiry.

While we may not be able to guess what someone is feeling or what their intent is, it is a sign that we should take care not to inadvertently accept someone’s point of view that we do not share.

It is essential to differentiate between questions meant to gather information and questions worded —intentionally or not— as disguised assertions. Genuine questions are open-ended and invite authentic responses. They allow for various perspectives and do not presume that the answer is already known. In contrast, leading questions limit the scope of the reaction and often reflect a hidden agenda.

The Impact of Safeness

We have noted Paul Gilbert's distinction between "safety" and "safeness". This distinction is subtle but essential, particularly regarding the emotional and psychological experiences necessary for formulating and responding to questions.

Safety typically refers to the absence of external danger or threat. It's about being free from physical harm or existential risks. On the other hand, safety goes deeper into the internal emotional and psychological experience. Even in the presence of a possible threat, it is more about how an individual feels within a space or relationship.

Safety is more about external protection, while safeness refers to an internal, emotional state of comfort, security, and, at minimum, temporary, conditional trust. You can feel "safe" from physical harm but still not feel "safe" emotionally or psychologically. Conversely, one may feel "safe" in a particular space but may not experience the internal comfort and openness that safeness provides.

Conclusion

The act of asking questions plays a pivotal role in human communication, particularly when navigating emotional states, human drives, and the goal of achieving effective interactions. By understanding the intricate connection between emotions and motivations, individuals can tailor their questions to foster openness, empathy, and clarity.

The right questions can bridge gaps, resolve misunderstandings, and promote deeper understanding in professional settings or personal relationships. Conversely, poorly constructed or leading questions may inadvertently steer conversations in unproductive directions, reinforcing biases or stifling authentic responses. Effective question-asking requires not only the awareness of one's emotional state but also sensitivity to the emotions and drives of others.

While based on science, ultimately, it is a hard-won Art. Different people feel differently and express themselves differently. And the same individual is more likely than not to respond differently in slightly different circumstances.

By recognizing the importance of context, emotional safety, and the underlying human drives that influence communication, individuals can enhance their ability to connect meaningfully with others, facilitating more productive, empathetic, and insightful exchanges. Thus, asking the right question is essential to fostering successful communication, and successful dispute resolution.

* Note: A pdf copy of this article can be found at:

https://www.mcl-associates.com/downloads/resolving_issues_with_your_boss_part6.pdf

References

Andersen, S. M., & Chen, S. (2002). The relational self: An interpersonal social-cognitive theory. Psychological Review, 109(4), 619–645.

Bradbury, T. N., & Fincham, F. D. (2002). Attributions and intimacy: A longitudinal analysis of marital interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(4), 640–654.

Clark, M. S., & Mills, J. (2011). A theory of communal (and exchange) relationships. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 165–227.

Cohen, F. S. (1929). WHAT IS A QUESTION? The Monist, 39(3), 350–364.

Dunning, D., & Kihlstrom, J. F. (2004). Personality and social cognition: Insights from individual differences in cognitive style. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(2), 51-93.

Gergen, K. J., McDonald, S., & Barrett, F. J. (2001). Dialogic collaboration: An integrative approach to group development. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5(2), 93–107.

Gilbert, P. (2024). Threat, safety, safeness and social safeness 30 years on: Fundamental dimensions and distinctions for mental health and well-being. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63, 453–471.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56(2), 109–118.

Neff, K. D., & Harter, S. (2002). The role of self-compassion in the development of social and emotional competencies. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 21(5), 627–654.

O’Connor, E. (2004). The role of self-questioning in educational contexts. Educational Psychologist, 39(1), 7–18.

Raskin, J. D., & Bridges, S. K. (2009). Questions about questions: Psychological perspectives on inquiry. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28(9), 1327–1346.

van Kleef, G. A., de Dreu, C. K., & Manstead, A. S. (2004). The interpersonal effects of emotions in negotiations: A motivated information processing perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(4), 510–528.

Watson, L. (2021). What is a question? Princeton University Press.

Figures:

© Mark Lefcowitz 2001 - 2025

All Rights Reserved

© MCL & Associates, Inc. 2001 - 2025

MCL & Associates, Inc.

“Eliminating Chaos Through Process”™

A Woman-Owned Company.

Business Transition Blog

No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise), or for any purpose, without the express written permission of MCL& Associates, Inc. Copyright 2001 - 2025 MCL & Associates, Inc.

All rights reserved.

The lightning bolt is the logo and a trademark of MCL & Associates, Inc. All rights reserved.

The motto “Eliminating Chaos Through Process” ™ is a trademark of MCL & Associates, Inc. All rights reserved.

While listening to an audiobook on the Medici by Paul Strathern, I was presented with a historical citation that I knew to be incredibly inaccurate. In a chapter entitled, "Godfathers of the Scientific Renaissance". discussing the apocryphal tale of Galileo's experiment conducted from the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the author cites Neil Armstrong in the Apollo 11 flight to the Moon with its memorable modern recreation, using a hammer and a feather.

Attributing this famous experiment to Armstrong on Apollo 11 is incorrect. It occurred on August 2, 1971, at the end of the last EVA of Apollo 15, presented by Astronaut Dave Scott. To press the point further, Scott used a feather from a very specific species: a falcon's feather. This small piece of trivia is memorable since Scott accompanied by crew member Al Worden arrived on the Lunar surface using the Lunar Module christened, "Falcon".

In an instant, the author's faux pas – for me -- undercut the book's entire validity. In an instant, it soured my listening enjoyment.

Mr. Strathern is approximately a decade my senior. As a well-published writer and historian, it is presumed that he subscribes to the professional standards of careful research and accuracy. Given this well-documented piece of historical modern trivia, I cannot fathom how he got it so wrong. Moreover, I cannot figure out how such an egregious error managed to go unscathed through what I assumed was a standard professional proofreading and editing process.

If the author and the publisher’s many editorial staff had got this single incontrovertible event from recent history wrong, what other counterfactual information did the book contain?

What is interesting to me, is my own reaction or -- judging from this narrative – some might say, my over-reaction to a fairly common occurrence. Why was I so angry? Why could I not just shake it off with a philosophical, ironic shake of the head?

And that is the point: accidental misinformation, spin and out-and-out propaganda -- and the never-ending stream of lies, damned lies, and unconfirmed statistics whose actual methodology is either shrouded or not even attempted -- are our daily fare. At some point, it is just too much to suffer in silence.

I have had enough of it.

God knows I do not claim to be a paragon of virtue. I told lies as a child, to gloss over personal embarrassments, though I quickly learned that I am not particularly good at deception. I do not like it when others try to deceive me. I take personal and professional pride in being honest about myself and my actions.

Do I make mistakes and misjudgments personally and professionally? Of course, I do. We all do. Have I done things for which I am ashamed? Absolutely. Where I have made missteps in my life, I have taken responsibility for my actions, and have apologized for my actions, or tried to explain them if I have the opportunity to do so.

For all of these thoughtless self-centered acts, I can only move forward. There is nothing I can do about now except to try to do grow and be a better human being in all aspects of my life. That's all any of us can do. I try to treat others as I wish to be treated: with honesty and openness about my personal and private needs, and when I am able to accommodate the wants and needs of those who have entered the orbit of my life.

We all have a point of view. Given the realities of human psychology and peer pressures to conform, it is not surprising that I or anyone else would surrender something heartfelt without some sort of struggle. However, we have a responsibility to others -- and to ourselves -- to not fabricate a narrative designed to misinform, or manipulate others.

Lying is a crime of greed, only occasionally punished when uncovered in a court of law

I am sick to death with liars, “alternative facts” in all their varied plumages and their all too convenient camouflage of excuses and rationales. While I am nowhere close to removing this class of humans from impacting my life, I think it is well past the time to start speaking out loud about our out-of-control culture of pathological untruthfulness openly.

Lying about things that matter -- in all its many forms, both overt and covert -- is unacceptable. When does lying matter? When you are choosing to put your self-interest above someone else’s through deceit.

Some might call me a "sucker" or "hopelessly naive". I believe that I am neither. Our species - as with all living things -- is caught in a cycle of both competition and cooperation

We both compete and cooperate to survive.

There is a sardonic observation, “It’s all about mind over matter. If I no longer mind, it no longer matters”. This precisely captures the issue that we all must face: the people who disdainfully lie to us – and there are many – no longer mind. We – the collective society of humanity no longer matter, if for them we ever did.

We are long past the time when we all must demand a new birth of social norms. We all have the responsibility to maintain them and enforce them in our own day-to-day lives. Without maintaining the basic social norms of honesty and treating others as you wish to be treated in return, how can any form of human trust take place?

Listen to the audio